— Explore why parents feel anger, what it reveals about unmet needs, and how Positive Discipline tools help create calm, connection, and lasting emotional growth. —

The Truth About Anger in Caregiving

Every parent feels angry sometimes — it’s human.

Parenting brings up some of our strongest emotions, often in the moments we least expect it. You might feel that rush of frustration when your child refuses to cooperate or does the exact opposite of what you just asked. And once the storm passes, regret or guilt can quickly follow.

In Positive Discipline A-Z, Jane Nelsen and her colleagues remind us that anger isn’t something to suppress or punish, but to understand and guide—first in ourselves, then in our children. Anger, after all, is part of being human. What matters most is how we handle it ⁷.

Adlerian psychology helps us take a step back from the surface behavior.

Rudolf Dreikurs, a key student of Alfred Adler, emphasized that behavior is purposeful. When we understand why our child (or we) react, we can respond with empathy instead of control ¹.

This shift—from judging the behavior to understanding the meaning behind it—is what turns a heated moment into a teachable one.

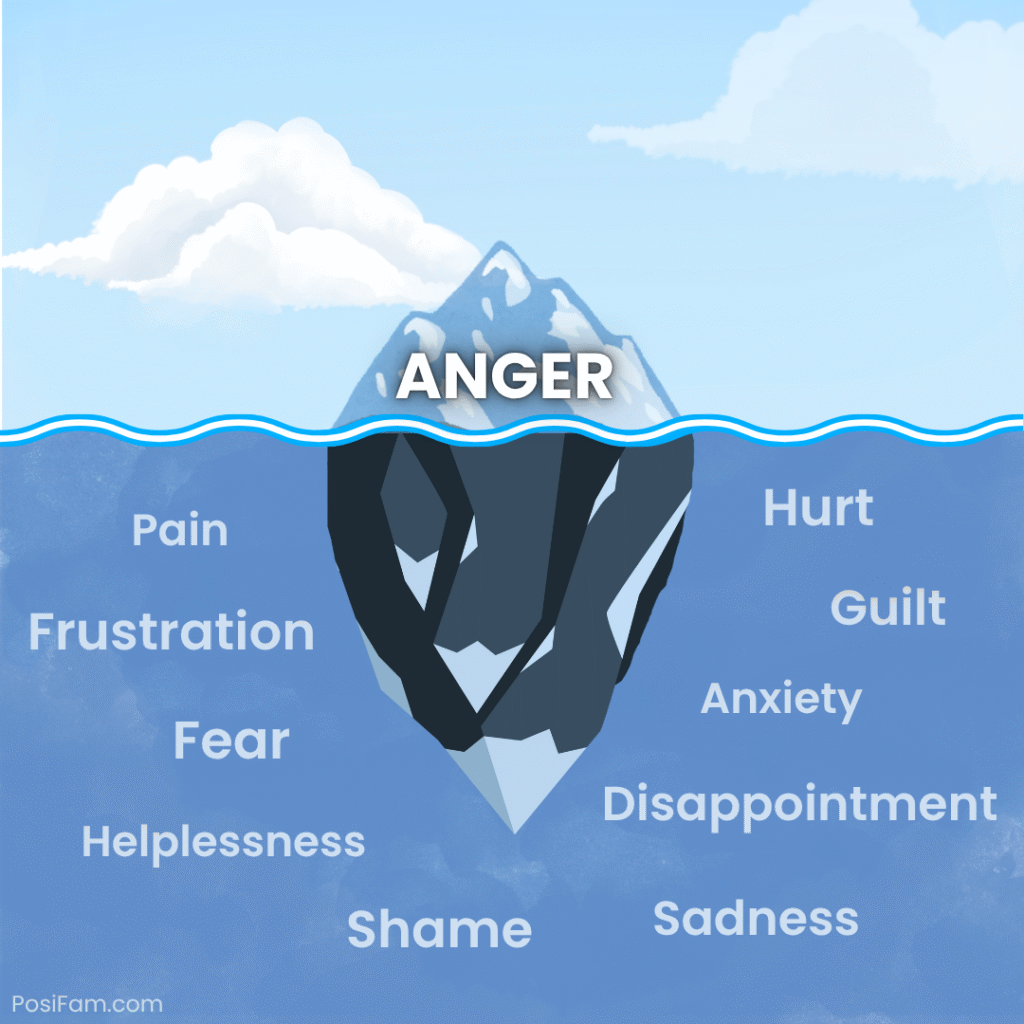

Understanding Anger as a Secondary Emotion

Many therapists and educators find it helpful to think of anger often as a secondary emotion—that is, often emerging from a primary feeling like fear, hurt or disappointment — though research shows anger may also appear as a primary, direct response⁶ ³.

When a child screams “That’s not fair!” or a parent snaps “Enough!”, anger may be a signal that deeper needs aren’t being met.

According to Adlerian psychology pioneer Rudolf Dreikurs, when we or our children act out, it’s often a response to a mistaken goal—an attempt to feel belonging or significance when we’ve temporarily lost that sense of connection².

Seen this way, anger becomes more than a “bad” feeling—it’s information.

It tells us something about where we feel powerless, disrespected, or disconnected. Once we recognize what’s underneath, we can start to reframe our thoughts, soothe our bodies, and model the emotional awareness we want our children to develop.

Digging Deeper: What’s Beneath the Anger — The Role of Belonging and Significance

When a parent feels disrespected, unheard, or out of control, anger often surges to the surface. But beneath that reaction lies something deeper: a momentary loss of belonging and significance.

In the Adlerian view, these two needs—to belong and to feel significant—are at the core of all human behavior. When they’re threatened, both adults and children experience emotional distress. That distress can show up as defiance, withdrawal, or yes, even anger.

In Positive Discipline, we often say that misbehavior is a mistaken belief about how to belong. The same idea applies to us as parents. When we interpret our child’s actions as disrespectful or dismissive, we may unconsciously feel disconnected or unappreciated. Anger becomes a quick way to protect our dignity, even though it often leaves us feeling regretful later.

By understanding anger through this lens, we can begin to ask new questions:

- “What am I really feeling underneath this anger?”

- “Do I feel unseen, powerless, or disconnected?”

- “How can I reconnect with my child—and myself—before responding?”

Recognizing these hidden needs doesn’t mean excusing harmful behavior, ours or our child’s. It means honoring the message behind the emotion. Once we identify what’s truly missing—belonging, respect, connection—we can respond from a calmer, more grounded place.

This understanding opens the door to one of the most powerful tools we have as parents: co-regulation. When we learn to calm our own nervous system first, our children’s brains—wired for connection through mirror neurons—naturally begin to follow our lead⁴ ⁵.

Co-Regulation and the Science of Connection

When a child is overwhelmed, angry, or melting down, it’s tempting to believe that reasoning or consequences will help. But in moments of stress, the brain’s survival system takes over—the amygdala signals danger, the body floods with stress hormones, and the part of the brain responsible for logic and empathy (the prefrontal cortex) temporarily goes offline.

In other words, when a child—or a parent—is in fight, flight, or freeze mode, no real learning can happen. Our words can’t be heard until the nervous system feels safe again.

This is where co-regulation comes in. Neuroscience now supports what Adlerian psychology and Positive Discipline have long taught: calm is contagious.

Research on mirror neurons, sometimes called the brain’s “empathy cells,” shows that our emotional states can literally influence those around us. When a parent slows their breathing, softens their tone, and grounds their body, a child’s nervous system begins to mirror that calm⁴.

“Our brains are wired for connection,” notes neuroscientist Marco Iacoboni in Imitation, Empathy, and Mirror Neurons (Annual Review of Psychology, 2009).

“We understand others by internally mirroring their emotions and actions.”

Therapist and educator Lisa Dion, founder of Integrative Somatic Psychology, calls this the science of safety. She explains that a parent’s regulated nervous system helps a child’s body feel safe enough to settle—long before any words of guidance can land⁵.

This process—called co-regulation—is how children learn to self-regulate over time. Emotional stability isn’t taught through lectures, but modeled through relationship. As Dr. Daniel Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson emphasize in The Whole-Brain Child, the developing brain needs repeated experiences of calm, connection, and repair to build the neural pathways for self-control and empathy¹⁴.

In short, our presence is the most powerful tool we have. Before we can guide a child, we must ground ourselves first.

When we understand this connection between our bodies, brains, and emotions, it becomes clear that regulation isn’t just about managing behavior—it’s about nurturing safety and trust.

And while staying calm in heated moments isn’t easy (especially when we’re tired or triggered), the good news is that regulation can be learned and practiced.

Just as children need time and guidance to build new skills, parents do too.

That’s why Positive Discipline offers practical tools—like Positive Time-Out, encouragement, and simple self-regulation practices—to help parents pause, reset, and reconnect before reacting.

Let’s explore what that looks like in everyday life.

From Reactivity to Regulation: Practical Tools for Parents

The goal isn’t to never feel angry—it’s to notice it sooner and choose what to do next.

These Positive Discipline–based tools can help you pause, reconnect, and respond with more calm when emotions run high.

a. Positive Time-Out (for Parents Too)

In Positive Discipline, “time-out” isn’t about sending a child away—it’s about taking a time-in with yourself. Dr. Jane Nelsen and her colleagues describe it as a respectful pause that lets both parent and child reset their nervous systems before trying to solve the problem⁷.

For parents, a Positive Time-Out might mean:

- Stepping away for a moment,

- Taking three slow breaths,

- Saying to yourself, “We’re both safe. I can slow down.”

When children see you take care of your emotions, they learn that it’s okay to do the same.

This is not withdrawal—it’s modeling self-regulation and emotional honesty.

🪴 Try this:

Say, “I’m starting to feel upset. I’m going to take a minute to calm my body, and then we’ll talk.”

That short pause can shift the entire tone of the moment.

b. A Family Calm-Down Space

Create a cozy, neutral spot where anyone can go to “take a break to feel better.”

Add comforting items—soft textures, soothing scents, quiet music, or books that calm the senses.

This isn’t a “go to your room” space. It’s a family-friendly environment that says, “We all need a moment sometimes.”

In Adlerian terms, it reinforces belonging and significance—the foundation of emotional safety¹ ².

When calm-down spaces are shared by everyone, not just children, they communicate: “You’re safe. You belong. We’re learning this together.”

c. Reframing Thoughts

Anger often hides other emotions underneath—hurt, fear, disappointment, or helplessness.

When we pause to name what’s really going on, we can shift from reactivity to curiosity.

Ask yourself:

“What am I really feeling right now?”

“What do I need?”

This small practice reflects Rudolf Dreikurs’ Adlerian insight that all behavior is purposeful—our reactions often point to an unmet need or mistaken belief about connection¹² ².

By reframing our thoughts, we begin to respond from awareness rather than impulse, teaching our children (and ourselves) that emotions are signals, not problems.

d. Encouragement Over Shame

Even with the best intentions, every parent loses their cool sometimes. What matters most is what happens after.

Instead of guilt or self-blame, try self-encouragement:

“I got upset, but I’m learning to pause sooner next time.”

Encouragement shifts focus from perfection to progress—it’s what Positive Discipline calls “seeing the good in yourself and your child.”

This models self-compassion and a growth mindset, helping children see that making mistakes is part of learning, not a reason for shame¹⁰ ⁷.

(Read more about Encouragement)

Parenting with regulation doesn’t mean staying calm all the time—it means practicing returning to calm, again and again.

Each moment you choose connection over control, you strengthen your child’s (and your own) ability to handle life’s big feelings with compassion and confidence.

🌸 These small shifts take practice. If you’d like more guidance on applying these tools at home, my 1-on-1 coaching sessions and workshops offer personalized hands-on support to foster more calm and connection in your home.

Why Punishment Doesn’t Help (and What Does)

Punishment may stop behavior in the moment—but research shows it doesn’t teach the skills children actually need for self-control or empathy.

Long-term studies, including one from McMaster University in Canada, have found that harsh discipline—even mild spanking—can increase anxiety, aggression, and depression.

At the same time, those same studies show that warmth, structure, and emotional safety predict resilience and cooperation in children⁸.

A longitudinal study published in JAMA Psychiatry also found that punitive discipline predicts higher stress responses in both parents and children, while emotionally supportive approaches strengthen connection and regulation⁹.

Positive Discipline takes a different path: connection before correction.

When we stay calm and focus on understanding what’s beneath a child’s behavior, we help them build the very skills punishment cannot—emotional regulation, problem-solving, and trust.

As Jane Nelsen beautifully puts it:

“Where did we ever get the crazy idea that in order to make children do better, first we have to make them feel worse?”

Children do better when they feel better¹⁰.

We can’t teach calm if we’re not calm ourselves.

When parents model regulation and kindness—even after mistakes—we show our children that safety and learning can coexist. That’s where real growth begins.

Closing Reflection

Anger doesn’t make you a bad parent, caregiver, or person. It’s a signal, not a verdict.

It often means something important needs attention—your boundaries, your exhaustion, or your need for support.

Everyone loses their cool sometimes. What matters most is what happens next. Each pause, each deep breath, each repair—these are moments of growth, both for you and your child.

When we practice self-compassion, we teach it too.

Children learn through our example that making mistakes is part of being human—and that calm, connection, and kindness can always be rebuilt.

It’s not about being perfect.

It’s about being present, learning alongside your child, and believing—just as Positive Discipline teaches—that every mistake is an opportunity to learn.

References

- Turning Point School. (n.d.). Dreikurs and children: The challenge. https://www.turningpointschool.org/dreikurs-and-children/

- ParentEducation Net. (2023). The child’s mistaken goals. https://parenteducation.net/the-childs-mistaken-goals/

- American Psychological Association. (2023). Managing anger. https://www.apa.org/topics/anger/control

- Iacoboni, M. (2009). Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 653‑670. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604

- Dion, L. (2023). Childhood regulation and neuroscience. Integrative Somatic Psychology. https://psychiatryinstitute.com/childhood-regulation-neuroscience-dion/

- The Gottman Institute. (2024). The anger iceberg. https://www.gottman.com/blog/the-anger-iceberg/

- Nelsen, J., Lott, L., & Glenn, H. S. (2007). Positive Discipline A-Z (3rd ed.).

- Foundation for Peaceful Parenting. (n.d.). The long‑term effects of corporal punishment. https://www.foundationforpeacefulparenting.org/the-long-term-effects/

- Lefkowitz, M. M., Huesmann, L. R., & Eron, L. D. (1978). Parental punishment. A longitudinal analysis of effects. Archives of general psychiatry, 35(2), 186–191. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770260064007

- Nelsen, J. (2015). Positive Discipline.

- Mori, K., et al. (2022). Maternal parenting stress from birth … and physical punishment to 10-year-olds: A population‐based birth cohort study (Tokyo Early Adolescence Survey). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35788880/

- Dreikurs, R., & Soltz, V. (1964). Children: The Challenge.

- Kohn, A. (2005). Unconditional Parenting.

- Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2011). The Whole-Brain Child.

Discover more from PosiFam

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.